When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established itself in Taiwan in 1624, it was not seeking to build a nation but to secure a foothold in Asia’s lucrative trade routes. Yet its brief rule marked Taiwan’s first formal incorporation into a global colonial system. For Indigenous peoples and later Han migrants, Dutch rule brought both violent disruption and new frameworks of governance that reshaped Taiwan’s emerging identity. Though the Dutch stayed less than four decades, their influence left structural and symbolic legacies that outlasted their departure.

To understand Taiwan’s development, the Dutch period cannot be dismissed as a mere interlude. It was the moment when Taiwan entered the orbit of global capitalism, when Indigenous life was forcibly restructured, and when the demographic seeds of Sinicization were sown. In this sense, the Dutch did not just extract resources — they set patterns that would be replicated by later empires.

By the early 1600s, the Dutch East India Company had emerged as one of the world’s first multinational corporations, wielding private armies, ships, and diplomatic powers (Andrade, 2008). Taiwan, located off the southeastern coast of China, offered several advantages. Its proximity to Fujian made it a convenient outpost for siphoning Chinese trade without direct confrontation with the Ming dynasty. Its fertile plains were ripe for sugar and rice cultivation. Its coastal position gave the VOC leverage over trade with Japan, a highly profitable market for silk and silver.

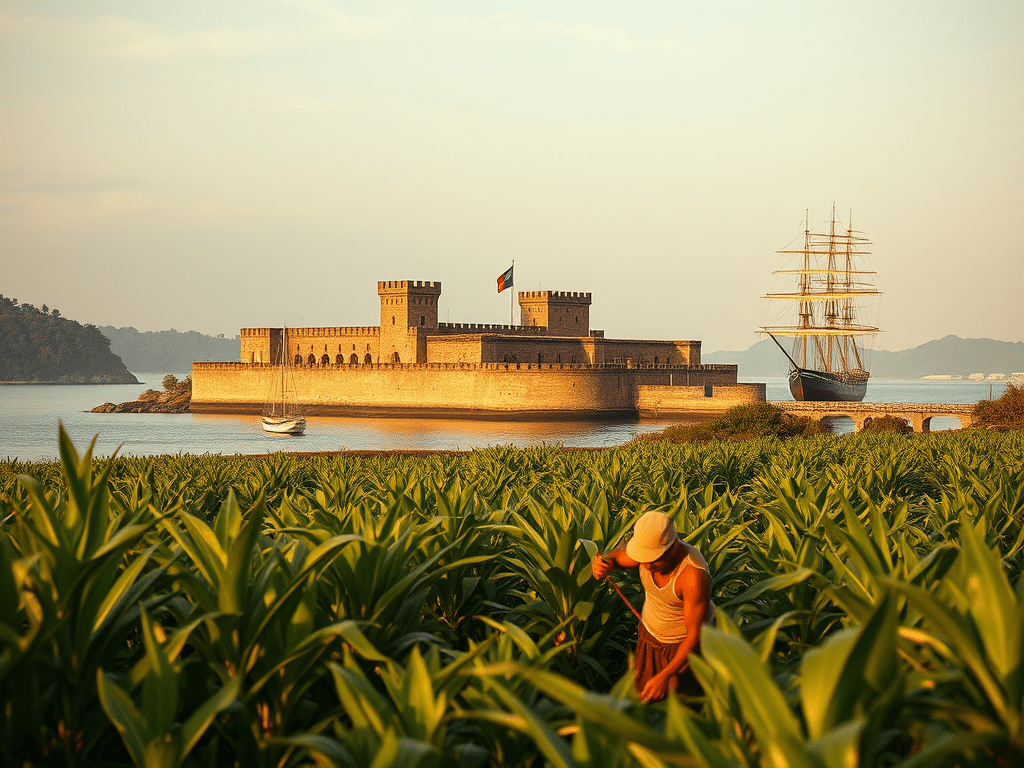

In 1624, after being expelled from Penghu by the Ming navy, the Dutch established Fort Zeelandia in present-day Tainan. From this stronghold, they sought to turn Taiwan into a maritime hub linking East Asia to Southeast Asia and Europe. The arrival of the Dutch was therefore not incidental — it was part of a broader effort to control the chokepoints of global trade.

Dutch Taiwan became an economic experiment in integrating Indigenous labor and Chinese migration into a global supply chain. The VOC organized the hunting of deer, a commodity highly sought after in Japan for hides and venison. More importantly, they promoted sugarcane cultivation, introducing techniques and systems of taxation that transformed Taiwan’s plains into export-oriented farms (Shepherd, 1993).

This economy depended on coercion. Indigenous peoples were pressured to provide labor, pay tribute, and surrender hunting grounds. Han Chinese migrants, who were initially seasonal sojourners, were incentivized to settle permanently as farmers. Over time, the Dutch administration began granting land rights to Han migrants, displacing Indigenous communities and intensifying frontier conflicts.

Through trade and taxation, the Dutch transformed Taiwan into a profit-generating colony, but in doing so, they set into motion demographic changes that would permanently shift the island’s ethnic balance.

The Dutch project was not limited to commerce. Protestant ministers sent by the Reformed Church saw Taiwan as fertile ground for conversion. Missionaries such as Robertus Junius pioneered a system of village schools where Indigenous children were taught to read and write in Romanized scripts of their own languages (Campbell, 1903/2012). The goal was not just literacy, but religious discipline. Sunday attendance was mandatory, and elders were fined or punished if children failed to participate.

This blending of education, religion, and governance was unprecedented for Taiwan. Literacy gave Indigenous communities new tools, but the price was cultural assimilation. Rituals, oral traditions, and autonomy were eroded. Resistance followed, most notably in the 1628 Mattau uprising, when an Indigenous coalition killed sixty Dutch soldiers. The VOC retaliated with overwhelming force, burning villages and executing leaders, an early example of collective punishment (Andrade, 2008). Christianization therefore functioned as both a spiritual and political project: it legitimized Dutch rule and imposed new hierarchies of obedience.

One of the most consequential outcomes of Dutch rule was the promotion of Han migration. Initially, the Dutch did not intend to populate Taiwan with Chinese farmers. But they soon realized that sustained agricultural production required permanent settlers. To this end, they encouraged migration from Fujian and Guangdong, granting land rights and legal protection in exchange for taxes and agricultural yields (Shepherd, 1993).

This policy had two effects. First, it entrenched a pattern of displacement for Indigenous communities, many of whom retreated into the central mountains. Second, it laid the groundwork for Taiwan’s eventual transformation into a Han-majority society. By the time the Dutch were expelled in 1662, tens of thousands of Chinese farmers had already established themselves. Thus, while the Dutch came as Europeans, their legacy was to accelerate Sinicization: a demographic shift that continues to define Taiwan’s identity today.

Dutch rule was never uncontested. In addition to Indigenous uprisings, the VOC faced external rivals. The Spanish briefly occupied northern Taiwan (1626–1642), and Chinese pirates routinely disrupted trade. Ultimately, the greatest threat came from Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), a Ming loyalist who, after losing the mainland to the advancing Qing, turned Taiwan into his base of resistance.

In 1661, Zheng’s forces besieged Fort Zeelandia. After nine months, the Dutch surrendered, marking the end of their 38-year experiment. Although their departure seemed to erase Dutch authority, the structures they built — from schools and forts to agricultural systems — continued to shape Taiwan under Zheng’s rule and later under the Qing.

What did the Dutch leave behind? Materially, they introduced new crops, trade systems, and fortifications. Culturally, they left traces of Christianity and literacy among certain Indigenous groups. Structurally, they pioneered the use of Taiwan as a colonial laboratory — an island to be molded for outside interests. Most importantly, they inaugurated a recurring theme: Taiwan as a frontier of empire, where Indigenous peoples were marginalized, settlers were imported, and the island’s identity was continually redefined by external powers. In retrospect, the Dutch period was short but foundational. It forced Indigenous communities into confrontation with colonial modernity, accelerated Han migration, and inserted Taiwan into the currents of global capitalism. Taiwan’s history as a contested, plural, and colonized island began in earnest under the VOC.

References

Andrade, T. (2008). How Taiwan became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han colonization in the seventeenth century. Columbia University Press.

Campbell, W. (2012). Formosa under the Dutch: Described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1903)

Shepherd, J. R. (1993). Statecraft and political economy on the Taiwan frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press.

Leave a comment