When the Spanish Crown expanded into northern Taiwan in 1626, it was not to build a colony in the conventional sense, but to secure a strategic outpost against their Dutch rivals. From Manila, the Spanish viewed Taiwan as both a military buffer and a religious mission field. The most enduring symbol of their occupation was Fort San Domingo in Tamsui, later known as the “Red-Haired Fort” (紅毛城). Though the Spanish presence lasted less than two decades, the fort they left behind became a multilayered site of colonial succession, encapsulating Taiwan’s history as an island repeatedly claimed, renamed, and reinterpreted by external powers.

Building the Red-Haired Fort

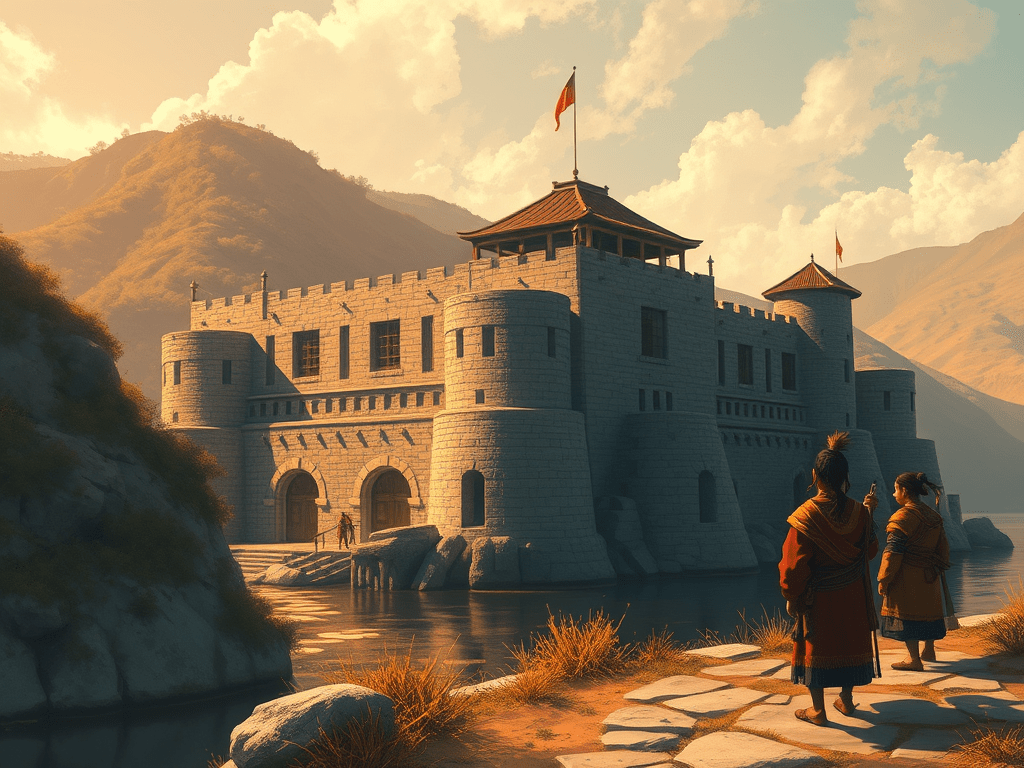

In 1628, two years after first landing in northern Taiwan, the Spanish began construction of Fort San Domingo at Tamsui. The location was carefully chosen: the Tamsui River provided a natural harbor, and the surrounding hills offered defensive vantage points. From here, the Spanish could monitor maritime traffic, protect their settlements in northern Taiwan, and counterbalance Dutch influence in the south (Andrade, 2008).

The name “San Domingo” honored the Dominican friars who played a central role in Spain’s colonial missions. Yet the local population had a different name: “Red-Haired Fort.” To the Indigenous peoples, Spaniards were identified by their hair color and appearance, a label later extended to the Dutch when they took the fort (Shepherd, 1993).

The fort was modest compared to Dutch strongholds like Zeelandia, but its thick stone walls symbolized the projection of Iberian power into Taiwan’s contested frontier.

Symbol of Evangelization and Control

Fort San Domingo was not merely a military outpost. It also anchored Spanish missionary activity. Dominican friars used the fort as a base to expand into Indigenous villages, seeking to convert local communities to Catholicism. Churches and schools were established in nearby areas, with mixed success (Blussé, 1999).

The presence of the fort gave missionaries protection, but conversion remained shallow. Indigenous groups often viewed Catholic rituals as foreign impositions, and Spanish authority was too thinly stretched to enforce religious discipline. Unlike the Dutch, who invested heavily in structured education, the Spanish approach was sacramental and episodic. As a result, Catholicism did not take deep root in Taiwan at this stage.

Conflict and Collapse

The Spanish presence in northern Taiwan faced constant challenges. They were under-resourced, reliant on Manila for supplies, and plagued by Indigenous resistance and Chinese pirate raids. Worse still, the Dutch, entrenched in the south, saw Spanish Taiwan as a direct threat.

In 1642, the Dutch launched a coordinated assault on Keelung and Tamsui. After a fierce battle, they captured Fort San Domingo, expelling the Spanish entirely from Taiwan (Andrade, 2008). The Dutch then rebuilt the fort, strengthening its walls and rebranding it as their own. For the local population, however, the name “Red-Haired Fort” endured, shifting from Spaniards to Dutch in popular memory.

Even though the occupation ended in 1642, the fort did not fade away:

- Dutch (1642–1661): After expelling the Spanish, the Dutch rebuilt the fort, reinforcing its military utility.

- Qing Dynasty (1683–1867): Following the Qing conquest of Taiwan, the fort was garrisoned, though it lost some strategic importance.

- British (1867–1972): In the late 19th century, the fort became the British consulate, with distinctive red-brick architecture added during this period. This association cemented the “Red-Haired” nickname.

- Modern Taiwan: Today, the fort stands as a national historic site and museum, a place my mom used to take me when I was small.

Spain’s time in Taiwan was brief and often overshadowed by the Dutch and later Qing rule. Yet through the Red-Haired Fort, the Spanish left a mark that transcended their short occupation. The fort became a canvas for subsequent powers, each layering their own ambitions onto its walls.

For Taiwan’s identity, Fort San Domingo is more than a relic. It illustrates how colonial encounters were remembered, adapted, and redefined over centuries. Spain may have lost Taiwan, but the structure they built continues to testify to the island’s status as a stage where global empires projected their power — and where local communities adapted to survive.

References

Andrade, T. (2008). How Taiwan became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han colonization in the seventeenth century. Columbia University Press.

Blussé, L. (1999). Bitter bonds: A colonial divorce drama of the seventeenth century. Brill.

Shepherd, J. R. (1993). Statecraft and political economy on the Taiwan frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press.

Leave a comment